.

George Krause: Interview. May 2018

.

TW: You had an exhibition recently in Philadelphia at the University of the Arts. What did returning to your hometown mean to you at this stage of your illustrious career?

.

GK: I have many great old friends in Philadelphia. An exhibition in Philadelphia offers me the opportunity to see as many of them as possible. My last exhibition in Philadelphia was in 2009 at the Plastic Club. There were a hundred faces I hadn’t seen in almost fifty years. Sad to say there were a few less in attendance at the opening at the UArts show in 2018. I was pleased to be invited by my alma mater to do a small introspective of work from the last sixty years.

.

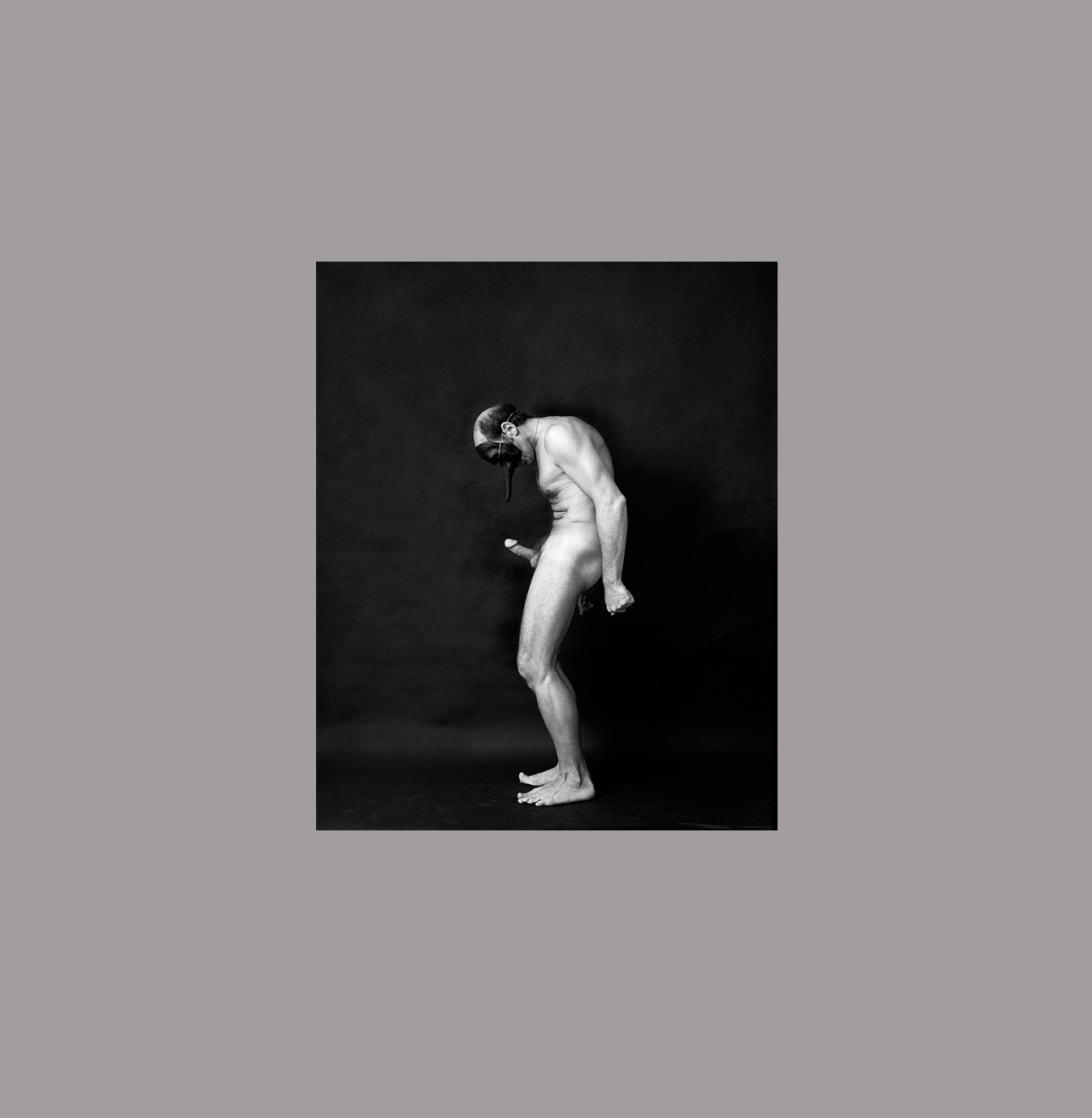

TW: What have you observed since you first began photographing people nude with respect to the issue of privacy and the obscenity laws in the USA?

GK: I don’t know the obscenity laws in the USA. I wrote the following for a book of essays collected by Andy Warhol’s right hand man Gerard Malanga. It has been referred to quite often.

From the book Scopophila: The Love of Looking by Gerard Malanga

Years ago I was accused by my wife of sleeping with all of the women who posed for me. My photographs suggested to her that I was getting more gratification out of photographing these nudes than just the making of images. This is perhaps the most common conception or misconception of voyeurism. I find it all but impossible to mix lovemaking with the act of making a photograph. But there is in fact a certain amount of seduction inherent, and for me necessary, in the making of a nude image, particularly a photographic image. Since my work often deals with fantasy, I want to create not only an ideal woman but a mythological woman of my dreams. This requires a talent, (unfortunately, one I’ve not yet fully developed) to transcend reality, which is helped greatly by encouraging in myself a fictional obsession and passion for the subject. The model in turn can respond with a desire to fulfill the artist’s attempt at transcendence or with a baser, narcissistic love for the attention being paid her, making love more to the camera than to the photographer. My wife’s accusations were, of course, not true, but when I thought about it I decided that it should be best if the photographer would photograph the woman (women) he was sleeping (in love) with. The accusation does reveal the artist /model fantasies imagined by those outside this collaboration. There is the erotic vulnerability of the undressed model with the dressed photographer (slave/master). At the first photographic session I’m nervous with the responsibility/obligation to the model to create something special and anxious with the potential fictional passion. In time I realize I can control the situation and the amount of desire needed to create the image I’m after.

The very act of peering through a small window to see a naked woman in the camera’s viewfinder suggests that of a Peeping Tom. There is the cowardice of distancing through the camera’s intervention to change the sexual reality of a nude woman into the context of a work of art. This is an attempt to sublimate the voyeuristic

nature of the nude. It is possible to increase the degree of distance in viewing a photograph of the nude by including another subject. This could be the photographer or other photographers. I am also thinking of the paintings of Susannah and the Elders. We may find it more acceptable to study the nude’s genitalia in the photograph when there are others included in the image for this purpose.

While an image of a woman nude may no longer evoke that of a fallen woman, a nude model today is perhaps considered a liberated woman, envied by some for her freedom in exposing her genitals and suspect by others for her morality or lack of it. This affects our take on the image.

I have shown my photographs of nudes to many art historians, and many of them have admitted difficulty in appreciating the nude in a photograph, in contrast to having no problem with the nude in other mediums (painting, sculpture, etc.). This suggests a special quality of voyeurism inherent in the “real” photographic medium.

Almost everyone approaches a photograph of a nude voyeuristically. We tend to compare our bodies with those in the photograph. There is a vicarious thrill of exposing ourselves in front of the camera. And there is the hint of a more intimate relationship between the model and the photographer. Photographers who place themselves in the image with the nude play with this reading. If the photographer is also nude and/or there is physical contact, this hint is underscored.

Photographs of nude models in poses that suggest the erotic demand a more immediate sexual interpretation. We are now back to peeking through the keyhole and there is always the danger of the voyeur being caught.

Generally, in viewing photographs of nudes we stand where the camera stood. The photographer has gone, and we are left alone with the subject of the image.

In working with the nude, we must realize the degree of unnaturalness that takes place. Even in a comfortable environment, the camera’s presence (and then our own) intrudes upon the nude, and when an awareness of technique (special lighting and camera effects) are added, along with our unwilling concern for props and costume, the intrusion must be that much greater. This, of course, can be deadly or these problems accepted and put to good use. The photographer can guide us as to how we are to react to the genitalia staring at us from the photograph, be it humor, fear, disgust, or even the pleasures of the voyeur.

.

.

TW: Are there any areas of the medium that have been under explored as a result of the longstanding position of the advertising industries stringent rules with respect to nudity and ad placement in mainstream magazines and online platforms?

GK: I’ve never had to deal as you have with the nude in advertising. I have had enough difficulty in the fine art end. I just recently had a couple of images censored by Instagram. I find it sad but also funny that my friend Spencer Tunick has to block out the genitalia of the thousands of participants in each of his images for Facebook.

.

TW: You taught for many years at the University of Houston. What was it about teaching that you enjoyed the most? The least?

GK: In almost every class I’ve taught there have been a few students that made coming to class a joy. From these students I and the other students learned a great deal. As photography classes became more popular, photography the passion, the excitement and work ethic declined. Unfortunately, in recent years I’ve found the majority of students far too complacent. They feel they know all they need to know and do not care for criticism: only praise. I often quote them the words of Robert Hughes “The greater the artist, the greater the doubt. Perfect confidence is the consolation prize awarded to the less talented”.

.

TW: As for legacy, would you be satisfied if history writes that “Fountainhead” is your Mona Lisa? If not, is there another picture from your various bodies of work that should be given equal treatment?

GK: Fountainhead is certainly in Philadelphia the favorite image, although it was originally rejected for use as a poster by the Bicentennial Committee. Other images that are as popular are The Shadow, which won first place in the recent Family of Man competition, Swish which has appeared on many more posters and propaganda, White Horse and Newspaper. It all depends on the time and place.

.

TW: Where were you when you received the call from the Museum of Modern Art when you learned that you would be included in John Szarkowski’s seminal text, Looking at Photographs? How did that inclusion impact the direction of your work after the publication date in 1973.

GK:Yes, it’s a great book and an honor to be included but even more important to me were earlier encounters with MOMA. The following is from an interview with SHOTS magazine that might help explain:

It is the dream of all art students to have their work, one day, hanging in a major museum. As students we all thought that if we worked and studied long and hard this might just be possible. In 1959 one of my teachers, Sol Libson who was one of the co founders of the Photo League along with Sid Grossman, suggested I take a portfolio of my work to show to the photography department at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. Edward Steichen purchased a few of my images for the study collection. In 1961 one of those images was included in a MOMA Recent Acquisitions show. A few years later, 1963, the new director, John Szarkowski in the first show he curated, invited me to be in the exhibition titled “Five Unrelated Photographers”.

.

TW: What was the most fun shoot or series of pictures you have ever produced?

GK: With out a doubt it is the San Miguel de Allende shoot in 2014. I photographed over a period of a few days a hundred lovely people in the nude, half over the age of sixty-five. These images became the exhibit “San Miguel Revelado” and was shown in 2015 at the Museo de Bellas Artes, a fifteenth century convent that is a world heritage site. In four rooms all connected by huge arches I hung sixty life sized nude images. Over eight hundred people attended opening night. Every day for three months more than two hundred visitors came to see the ex convent and my show.

.

.

TW: If you could give a single piece of advice for the young shooter that wants to survive solely on making pictures for a living, what would it be?

GK: If you have a vision that drives you to make images I think it is better to find another occupation that does not conflict with your vision. I have worked at so many jobs to support my personal work. Some of these jobs involved photography in advertising, journalism. I did not find it too difficult to solve the demands of others. The great challenge for me has always been to search for the answers to my own questions. There have been a few rare assignments from friendly art directors that led to an image or two that answered both our needs. But not many. I taught for many years and found I was concerned more about the student’s vision than my own. My advice, not a facetious as it may sound is to find a rich patron.

.

TW: What are your impressions of the digital revolution and its impact on the Fine Art of photography?

GK: I think we are still at the beginning of understanding what this new technology can tell us what we are about. For me the impact has been more physical. I can no longer put in the long hours in the darkroom developing thousand of rolls and sheets of film. I have a new knee and hip to go with my new eyes and I hope to travel once more with a much smaller and lighter camera bag. The digital revolution came just at the right time in my life.

.

TW: What is your relationship to Frank- besides the obvious- and when were you first introduced to this grand master of the craft?

GK: I was invited to write as were almost 200 other photographers a tribute to celebrate Frank’s birthday in the 2016 edition of the Americans List. Below is my contribution:

In 1957 I was a student in my third year at the then Philadelphia Museum School of Art. I had studied printmaking, advertising and graphic design with one basic fundamentals of photography class thrown in for good measure.

Feeling unsure of my career path and the pressure of the compulsory draft into the army, I enlisted at the end of my junior year. I dreamed of being stationed overseas in Europe for two years, returning wiser and better-focused for that final year.

Instead I was assigned to South Carolina as a clerk in a Counter Intelligence Unit. A position at which I did not excel and certainly not the tour of duty I had imagined for myself. London, Paris, Berlin… Columbia SC?

One day while at the files I noticed one of the agents holding a small object in his hand and a puzzled look on his face. I immediately recognized it as a Weston photographic light meter. I pushed the low light button, the needle moved and from that moment on I was the photographer for the Counter Intelligence Corps.

And then came the rumors of Robert Frank’s The Americans. This controversial book with its harshly criticized images defying many of the conventions of the times and seen by so many as depressing and negative, inspired me to dream of a Guggenheim and the chance to discover my own America.

In the early 1960’s the burning question in the art world was “Is photography art?” Clement Greenberg—a leading art critic of the time— decided to answer this once and for all. “No” he declared “Photography was incapable of creating a serious work of art”. Robert Frank and his The Americans so forcefully helped refute that now-discredited position.

It is a difficult choice as a favorite but I keep coming back to Trolley-New Orleans, the photograph reproduced on the dust jacket, the very first Robert Frank image I saw. It is a perfect combination of abstract formal design (those crazy reflections in the windows above) and photographic reality (great faces in subjective eye contact) that together make the image and it’s social statement so powerful.

.

TW: What is a typical day like for George Krause these days? Any new projects on the horizon that TWS readers will be the first to read about?

GK: I work on new images, edit old images and like to think I have begun to write my “memoirs”. Someday soon I will do a book on the Sfumato series.

.

.

George Krause was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania in 1937 and received his training at the Philadelphia College of Art. He received the first Prix de Rome and the first Fulbright/Hays grant ever awarded to a photographer, two Guggenheim fellowships and three grants from the National Endowment for the Arts.

Krause’s photographs are in major museum collections including the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, The Philadelphia Museum of Art, and the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris. In 1993 he was honored as the Texas Artist of the Year.

He retired in 1999 from the University of Houston where in 1975 he created the photography program and now lives in Wimberley, Texas.

.

To access additional articles about George Krause, click here: https://tonywardstudio.com/blog/george-krause-lunch-with-a-legend/

To access George Krause’s web site, click here: https://georgekrause.com

.

All Rights Reserved. Copyright, George Krause 2025.